It was not long ago when former U.S. national security adviser, John Bolton, now the subject of a Congressional investigation involving President Donald Trump, gave a speech outlining America’s new Prosper Africa strategy. Speaking at the Heritage Foundation in Washington D.C. on December 13, 2018, Bolton said, “The White House is proud to finalize this strategy during the second year of President Trump’s first term, about two years earlier than the prior administration’s release of its Africa strategy.” This statement came right at the top of his speech.

Bolton Makes an Announcement

Saying the administration was rolling out its Africa strategy earlier than the Obama administration was note-worthy. In a sense, it meant they wanted to make this a priority.

Many analysts took Bolton’s words for what they were – something new from a new, incoming U.S. administration. The speech, which was described as fiery, made the news rounds, with diverse interpretations, especially about an administration headed by a president who is still viewed negatively by Africans on the continent and in the diaspora.

After all, it was Trump himself, who said during his inaugural address that America was spending trillions of dollars overseas building other nations while its infrastructure was in decay. Trump’s goal was to change things in Washington. His America First policy, designed to put American interests ahead, was going to take precedence over everything the country was involved with.

New U.S. Prosper Africa Strategy

A few days after Bolton’s speech, on December 18, Michael Shurkin, a political scientist at the Rand Corporation, dissected the new U.S. Africa strategy with this review.

On the positive side, he wrote, “Bolton identified “three core U.S. interests:” promoting U.S. economic interests in Africa, countering Islamic extremist terrorism and ensuring that U.S. taxpayer dollars devoted to aid and U.N. operations in Africa are not wasted. All of these are sound.” On the negative side, Shurkin said, “The problem with his speech was an implied fourth priority that appears to overshadow all others, that of competing with China and Russia for influence. The topic came up amid his discussion of commercial interests, which he used as a platform for diving into a relatively lengthy discussion about “predatory” Chinese and Russian practices.”

Before Bolton outlined Trump’s Africa strategy, earlier in March, then secretary of state, Rex Tillerson made a week-long trip to the continent during which he visited five countries, including Ethiopia and Nigeria, considered strategic U.S. partners.

On the administration’s Africa plans, Brahima Coulibaly, an analyst at the Brookings Institution said there was still time for the administration to build its own Africa legacy and he hoped the trip Tillerson made was the beginning of an important step toward dialogue with the continent.

Melania Goes to Africa

But just before all of this, in January 2018, the President was accused of using derogatory language to describe African nations during a meeting with congressional leaders at the White House. Trump denied he ever denigrated African nations. That was before Tillerson traveled to the continent and before Bolton unveiled the administration’s Africa policy.

Then in October, first lady Melania Trump made a solo trip to four African nations – Ghana, Malawi, Kenya, and Egypt.

Melania Trump in Egypt on Saturday. Her trip, she said, was meant to “show the world that we care.”Credit…

Commenting on why Trump may have chosen the continent for her first solo international trip, Kate Bennet of Cable News Network (CNN) wrote, “The mere fact that Trump chose Africa for her inaugural solo international trip when her husband’s reported derogatory remarks about certain countries here set off a firestorm of controversy earlier this year, demonstrates at least a certain amount of desire on her part to put a face to an administration whose leader is not seen as particularly benevolent.”

While there was optimism in some quarters about the overall Africa posture from the administration– talking and connecting with the continent, building relations through visits, showing interest by having goals and objectives, there remained plenty of doubts as well. African experts from all backgrounds, and Africans themselves, adopted a wait-and-see attitude toward the administration. Maybe things would improve, many thought – perhaps the public sentiments – what you see and what you hear from Trump and his people about Africa – would get better.

Policy Goes From Minus C to Minus F

Since then, Tillerson and Bolton were unceremoniously dismissed by Trump, a president considered erratic by people who have been close to him. And there is a whole slew of people engineering the U.S. – Africa policy at the White House and at the State Department, and making perceptions about the administration even worse through their decisions and choices.

Going back to 2017 when the light began to shine on the administration and its African policies, the South Africa Institute for International Affairs published a study on the continent’s response to the administration. The lead author of the study is John Stremlau, a visiting professor at the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa. The Council on Foreign Relations John Campbell thinks the study is a “thoughtful and devastating critique” of the Trump administration. Campbell is a former U.S. ambassador to Nigeria.

“The report contains in one place a great deal of information, ranging from the impact of proposed budget cuts at the State Department on Africa to cataloging public statements about Africa made by the president (almost none), the secretary of state (also almost none), and Nikki Haley, U.S. ambassador to the UN (a significant number). He also shows how remarkably little interaction there has been between the president and the secretary of state and African leaders,” Campbell wrote in 2017.

Trump Gives with One Hand – Takes Back with Another

Since Bolton’s speech outlining the administrative approach to the African continent, Tillerson’s trip, as well and Melania’s much-heralded trip, a host of other things have happened, including the passage of the BUILD act. Bi-partisan legislation passed by Congress in October 2018, the act led to the creation of a new U.S. development agency, the International Development Finance Corporation(USIDFC). Daniel Runde and Romina Bandura, both of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, believe it is part of the response from the United States to the challenge of China in the African continent.

With the BUILD act, it is Congress that is taking the lead in formulating U.S. Africa-Africa, not the Trump administration, Witney Schneiderman, a fellow with the Brookings Institution said at the time. “While the Trump administration has yet to formulate a policy toward the region, Congress has stepped up in a strong bipartisan manner to play a pivotal role in promoting U.S. interests in Africa, especially as it concerns women, the private sector, and economic development more generally.

US Trade Deficits with Africa

While we can’t judge policy successes simply by looking at the headlines they generate, these reports don’t bode well for the administration and whatever they are trying to do. This may be why not too many analysts have given the administration much kudos for anything they have done. A Congressional Research Service report, a service of the U.S. Congress, says it is very much up for debate whether the administration’s Prosper Africa initiative can help double U.S. trade with the continent.

“Past Administrations have similarly sought to expand U.S.- Africa trade and investment ties, but gains to date have been modest. In 2018, Africa accounted for 1.6% of U.S. global trade and 0.8% of U.S. foreign direct investment— about half the level recorded in 2010, the peak year for such measures over the past decade. These trends suggest that achieving significant trade and investment growth may not be easy.”

A Lack of Strategy

While Bolton unveiled Prosper Africa in December 2018, it took almost a year to begin its implementation.

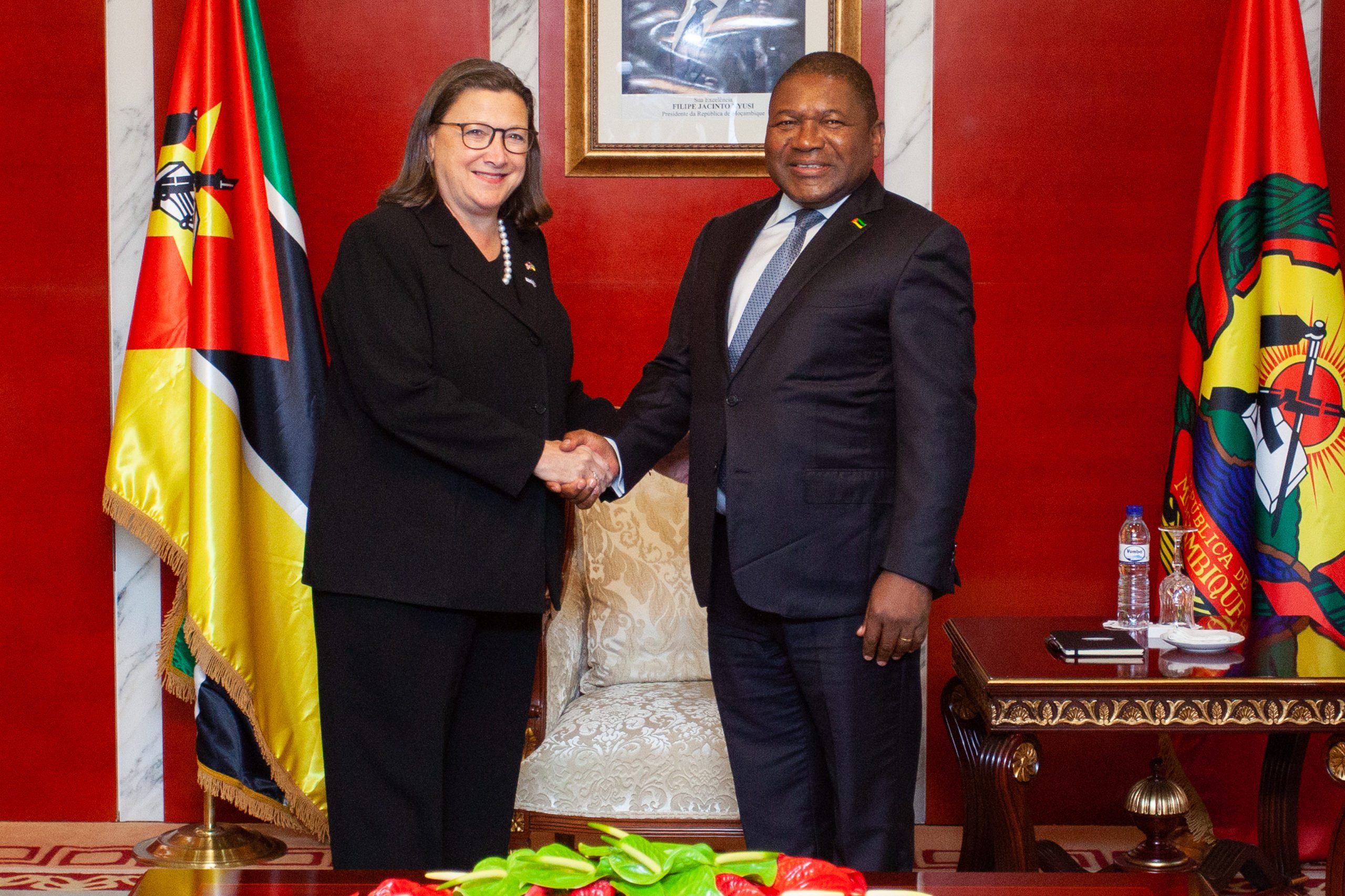

When R. Riva Levinston, CEO of KRL International, a Washington D.C.-based consulting firm and a contributor to The Hill, traveled to Maputo, Mozambique in June of 2019 for the roll-out of a strategy meant to counter China in Africa, at first, she was not impressed. She says she grumbled when she realized the irony of having officials from U.S. government agencies assembled under a building that China built.

While critical that America lost ground in the continent to China and Russia, Levinston says there is an opportunity to get into the game. She writes, “Within this context, let us recognize Prosper Africa for what it is — an effort to get the U.S. into the commercial game on a continent where combined consumer and business spending is expected to reach $6.7 trillion by 2030.”

No Leadership at the Top

Kimberly Ann Elliott, a visiting scholar at the George Washington University in Washington D.C. says there are plenty of reasons for African governments to be concerned about the administration.

One of those reasons is what she considers a low-level U.S. engagement with the continent. She says Trump has not visited the continent, and while his wife and daughter have, those trips, she says, were mere photo ops and light on policy. She also questions why Wilbur Ross, Trump’s commerce secretary, canceled his trip to the U.S.-Africa Business Summit in Mozambique where the details of the Prosper Africa Plan were going to be announced. However, the administration was represented by deputy commerce secretary, Karen Dunn, the United States for International Development (USAID) administrator, Mark Green, assistant secretary of state for African affairs, Tibor Nagy, commerce under-secretary, Gilbert Kaplan, among others, according to this report from the Brookings Institution.

US Double Standards

Even more, Elliott says she sees what may seem like a double standard in the administration’s Africa policy proposals.

“The $50 million proposed budget for Prosper Africa is a drop in the bucket compared to the administration’s proposed 9 percent cut in overall aid to Africa. And efforts to negotiate bilateral trade agreements country by country would undermine the regional integration that is needed for the continent’s development,“ she writes on World Policy Review.

Beyond these proposals and initiatives is the January of 2020 travel ban the administration placed on four African nations – Nigeria, Eritrea, Sudan, and Tanzania.

“The effect on Nigeria, not only Africa’s most populous country but also its largest economy, could be particularly severe. The United States issued more than 7,920 immigrant visas to Nigerians in the 2018 fiscal year, the second-most of any African country,” Zolan Kano-Youngs writes for the New York Times on January 31.

Nigeria Takes a Hit

In a February 4 Washington Post story, Trump Scapegoats almost a quarter of Africa’s population, Ishaan Tharoor writes that there’s more pronounced anger and disbelief among Nigerians following the travel ban. He says Nigerian politicians have gotten involved, with some of them venting their frustrations on Twitter. Citing the Council on Foreign Relations’ John Campbell, the writer adds that the ban poses risks for an administration that appeared eager to build relations with the continent’s major economies.