Philippe Rey

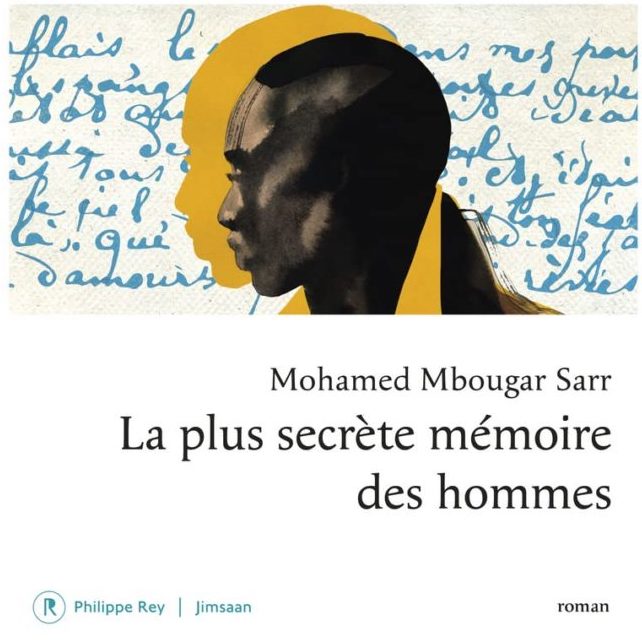

Philippe Rey A caption displaying the title of Mbougar Sarr’s book that won the 2021 Goncourt Prize.

The prestigious 2021 Goncourt Prize has been won by Mohamed Mbougar Sarr, with his novel “La plus secrète mémoire des hommes”, or “The most secret memory of men.” The book was published in France by Philippe Rey.

Mohamed Mbougar Sarr thus became the first writer from sub-Saharan Africa to receive France’s most prestigious literary prize. At only 31-years-old, he is also one of the youngest winners since Patrick Grainville in 1976.

Mbougar Sarr was born in Senegal in 1990 and moved to France to study literature and philosophy at the École des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris.

Previously Mbougar Sarr won several awards, including the Stéphane Hessel Prize for his novel “La cale” (2014). He published “Brotherhood”, a novel that earned him the Ahmadou Kourouma Prize at the age of only 25.

From Senegal to France, via Argentina, what truth awaits him at the center of the labyrinth?

These are some of the questions emanating after this big achievement for Mbougar Sarr.

“By winning the coveted Goncourt Prize, the young writer Mohamed Mbougar Sarr has honored Senegal and Africa,” said Senegalese Minister of Culture and Communication, Abdoulaye Diop, commenting on the decision of the jury of the prestigious francophone literature competition to award the 2021 victory to the novelist.

In a statement, the minister recalled that exactly a century ago, René Maran, then the administrator of a colony in Oubangui Chari, won this prestigious award for his timeless novel, “Batouala”. It was in 1921 that René Maran (Fort-de-France 1887 – Paris 1960) became the first writer of African descent to win the Goncourt Prize. His novel Batoula, symbolically marked the beginning of the struggle undertaken by various intellectuals to defend and reclaim indigenous cultures.

Minister Diop said that Senegal is not surprised because “Mohamed Mbougar Sarr, who, with the humility and smiling tenacity of the sons of the Earth, has always and regularly entertained us with works of such exquisite quality, with a wealth of themes drawn from experience and memory, and richly framed by an intertext based on an impressive literary culture”.

The author, he added, represents “the pride of the whole of Senegal through the achievement of this son of a land, that of Léopold Sédar Senghor and Cheikh Moussa Ka, where literature, in all its forms, has long taken up residence”. “In the name of the Head of State and all the Senegalese people, Abdoulaye Diop extended his “warmest congratulations to Mohamed Mbougar Sarr (…) for having raised so high the image of our literature and our creativity”.

This win is not just a victory for Sarr. We are in a new era for African literature and especially for the reconstruction of a normalizing perception of Africa in the rest of the world.

The Goncourt Prize is a great achievement for all francophone writers. This prize underlines the hegemonic power of the French state over francophone countries, how they must somehow always be dependent on them as if it were the only way to make francophone literature known to the rest of the world. Despite this, it is also worth remembering that African literature does not always have to depend on these Western prizes, but exists independently of these victories.

The evolution of Africa is often overshadowed, and people prefer to recount the drama rather than the positive changes the continent and its people experience. It is important to reflect deeply on this issue, especially on how the continent emerges from this narrative and why we ourselves are almost surprised to hear of the victory of a Senegalese author on this prestigious award.

Hence the need for new rules for coexistence between cultures in the world, and how this can be made so small by the media. The simplistic representation of the continent and its people is absolutely indefensible. This news may be a small consequence of the continent’s distorting narrative.