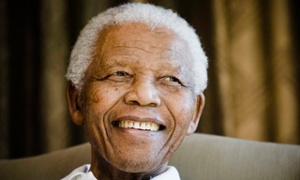

There is a saying from my home of Nso (in the North West Region of Cameroon) that what is regrettable is death in life, not clinical death itself.” As an African I am touched, as are many people from around the world, by the death of Nelson Mandela popularly known in South Africa as Madiba.

What is particularly striking is why so many around the world have been so moved by both Mandela’s life and death.

For many, his greatness lies in his Moses-like role in leading his people from the bondage of apartheid to a state of freedom without the bloodshed and violence that many anticipated would ensue. But this simple single storyline is not all, since it is clear that the demise of apartheid was the work of many, including Mandela’s fellow Nobelist F. W. De Klerk and countless others.

Mandela’s truly unique claim to greatness rests not on his management of the transition out of apartheid and assumption of power – although that is undoubtedly a central part of his legacy. Nor is it really a matter of what he did with that power when he held it—although what he did with it was extraordinary.

The true source of Mandela’s greatness is how he gave up that power. It was his exit—dignified and orderly—more than anything else that sets him apart. His exit from office at the height of his power, popularity, and health put him in the company of Cincinnatus of ancient Rome and George Washington — exemplars of the rule of law and the ideals of leadership in a republic.

These are men from different times who faced very different challenges and obstacles, but what they shared—and what keeps them alive—is their audacity to have ceded power and exited the political cockpit of their own accord at a time when many wanted them to continue on.

It is the utterly surprising nature of such leaders that makes them great, for nothing corrupts more than the pleasure of power and those entrusted with power come to appreciate its attractiveness, sweetness and lure, and so nothing in politics is more honorable and surprising than this very act of exit.

To give up political power is no small matter. What differentiates democratic constitutions from other systems of governing is the ability to lose and still remain faithful to the governing framework and to his or her successor. The inauguration of a new leader is as much an exit of the old as the entrance of the new, and not surprisingly, elaborate rituals, symbols and civic sacraments have developed around transitions of power in democracies to smooth the transition from one to the other. Such traditions and civic lessons are typically learned through repetition, habit, and example.

For South Africa—and for millions of others throughout Africa and the rest of the developing world—Mandela was the example, teaching through his actions that politics is an honorable art and reconciling them to being governed and giving them reason to feel that, win or lose—and especially and particularly lose—the system is theirs.

The Mandela exit may not strike many in the West today—whose constitutional devices and traditions enable leaders to enter and exit as if at ease—as extraordinary but in the continent of Africa where a “vote from heaven” (or death in office) was and continues to be the surest way to wean leaders from power, Mandela stands out.

This is, after all, a continent in which billionaire Mo Ibrahim, the Sudanese-British mobile communication entrepreneur, has offered African leaders a $5 million down payment and $2,000 annual stipend for life if they voluntarily leave office when voted out through elections

It is also a continent that is bewildered by the attachment of leaders to the office entrusted to them by the people. I, too, thought that Africans should institute gerontocracy with an eighty-five years minimum age requirement for the highest offices of the land and then leave heaven to vote them out of office.

Editor’s Note: Another version of this story appeared in the Denver Post on December 8.